Alert

A Presumption of Unaffordability: The CFPB’s Proposed ATR Standard

Read Time: 1 minThis article is the second in a series discussing the CFPB’s recently-issued Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, which would cover Payday, Vehicle Title, and Certain High-Cost Installment Loans (the “Rule”). This article will discuss the Rule’s ability-to-repay (“ATR”) standard for covered loans.

Recall that a covered loan is any short-term loan with a term of 45 days or less; and any “longer-term” loan with a term of more than 45 days, where the total cost of credit exceeds 36% per year and the lender obtains either: (1) a security interest in the consumer’s vehicle, or (2) a “leveraged payment mechanism.” See our earlier article for a brief description of “leveraged payment mechanisms,” which we will revisit in more detail in a forthcoming article.

The ATR standard is largely the same for short and longer-term loans. So unless specifically noted, this discussion of ATR will not distinguish between them. In short, the Rule provides that a lender must not make a covered loan or increase the credit available under a covered loan, unless the lender first makes a reasonable determination that the consumer will have the ability to repay the loan according to its terms. This means lenders must perform consumer cash flow analyses—with a few moving parts.

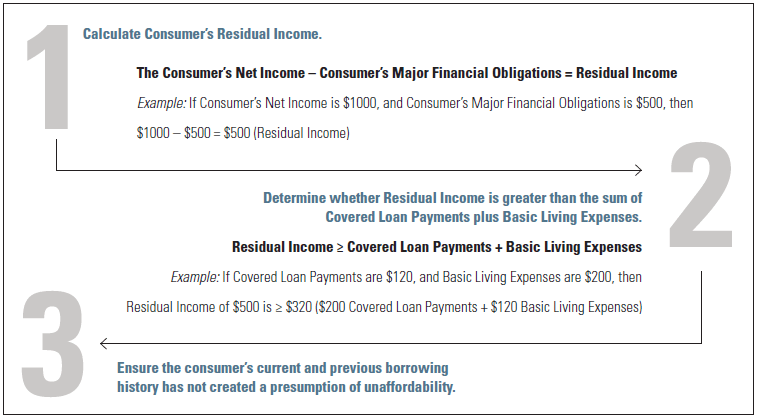

Three Basic Steps to a Consumer Cash Flow Analysis

Obtaining Evidence of ATR

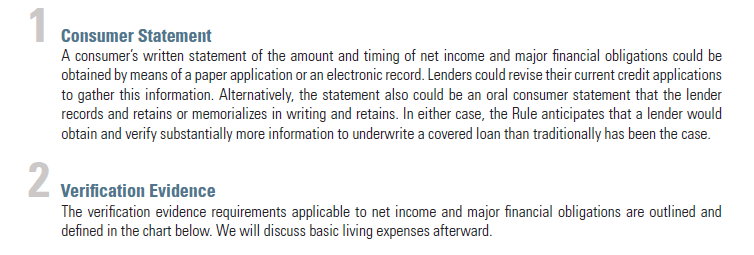

Before conducting any analysis, ATR or otherwise, some basic facts—or, “evidence”—are required. The Rule would require lenders to obtain evidence that includes: (1) a consumer’s statement of the amounts and timing of net income and major financial obligations, and (2) extrinsic “verification evidence” supporting the consumer’s statement.

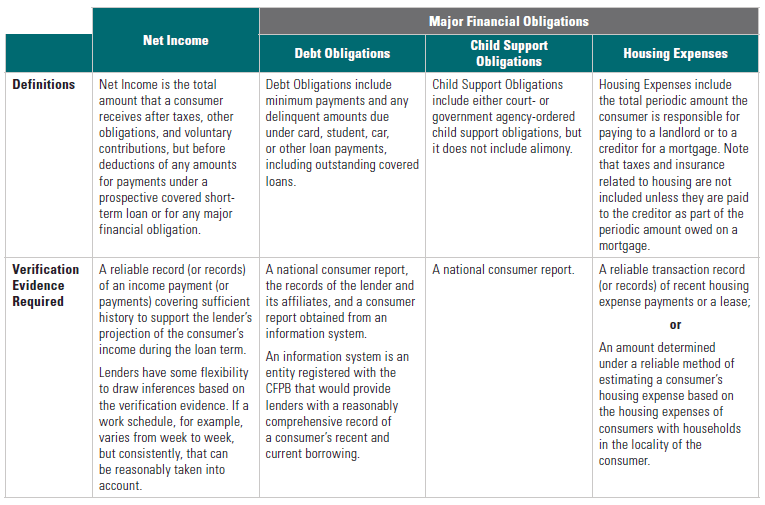

Evidence of Net Income and Major Financial Obligations

A lender could project a Net Income amount that is higher, or a payment amount under a major financial obligation that is lower, than an amount that would otherwise be supported. However, this is only permissible when the lender obtains a written statement from the consumer’s employer, or the recipient of the consumer’s major financial obligation, of the amount and timing of the new or changed net income or payment.

Additionally, a lender would be required to account for other information that is known by the lender, even if it is not required by the Rule. For example, if the lender learned that a particular consumer had an unusual expense significantly above the amount used to estimate basic living expenses, the lender would not be able to simply ignore that fact.

Defining Basic Living Expenses

Unlike major financial obligations, lenders would not be required to obtain evidence documenting a consumer’s basic living expenses. Basic living expenses are expenditures, other than payments for major financial obligations, that a consumer makes for goods and services necessary to maintain the consumer’s health, welfare, and ability to produce income, and the health and welfare of members of the consumer’s household who are financially dependent on the consumer.

Essentially, this would include everything other than child support, housing, and loan payments. The Rule specifically includes food, utilities, transportation, and child care as examples. However, basic living expenses could also include clothing, medicine, entertainment, and so on—anything a typical consumer would typically buy.

Lenders could identify basic living expenses by asking consumers to list their basic living expenses on the application. Alternatively, the Rule would allow lenders to develop a methodology to calculate the appropriate figure. The guiding principle is that this calculation must not be so low that it is unreasonable for consumers to pay for the types and level of basic living expenses.

Guidelines for Crafting Policies and Procedures

The Rule would require lenders to create and follow written policies and procedures that are reasonably designed to ensure compliance with the ATR calculations and verifications described above. Among other things, the policies and procedures should specify a lender’s business model and practices, including the particular methods it uses to obtain consumer statements and verification evidence; how lenders project consumer net income and payments for major financial obligations; and the underwriting conclusions that the lender makes based on information it obtains. The CFPB envisions that lenders would be able to automate application of those policies and procedures for most consumers.

Determining Residual Income and ATR

A lender would not be required to perform an ATR determination if it declined to extend credit for other reasons—fraud, for example. Otherwise, a lender must reasonably assess ATR prior to making a covered loan, increasing a covered loan’s available credit, or allowing a consumer to obtain an advance under a line of credit 180 days after the previous ATR determination.

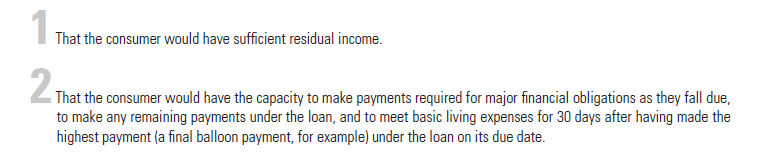

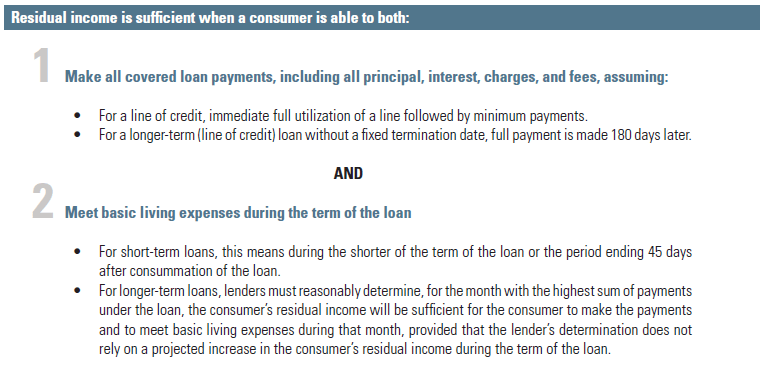

As noted above, a reasonable ATR would be based on projections of the consumer’s net income, major financial obligations, and basic living expenses. It would map the timing of cash inflows and outflows so that a lender could reasonably conclude two things:

Conceptually, the CFPB’s vision is straightforward. If a consumer has less money coming in than going out, the consumer does not have an ability to repay the loan. If a consumer gets a paycheck, pays the mortgage, pays a credit card bill, and then repays a covered loan, will the consumer still be able to eat and get to work? And next month too? If so, the consumer has the ability to repay. The practical difficulty is building into the analysis all required assumptions and ensuring the timing and amounts of income and payments are accurate. The philosophical difficulty is substituting a formula for an individual’s judgment about what is right for his or her circumstances.

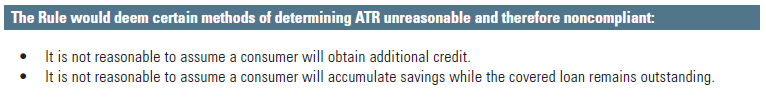

Unreasonable Methods for Determining ATR

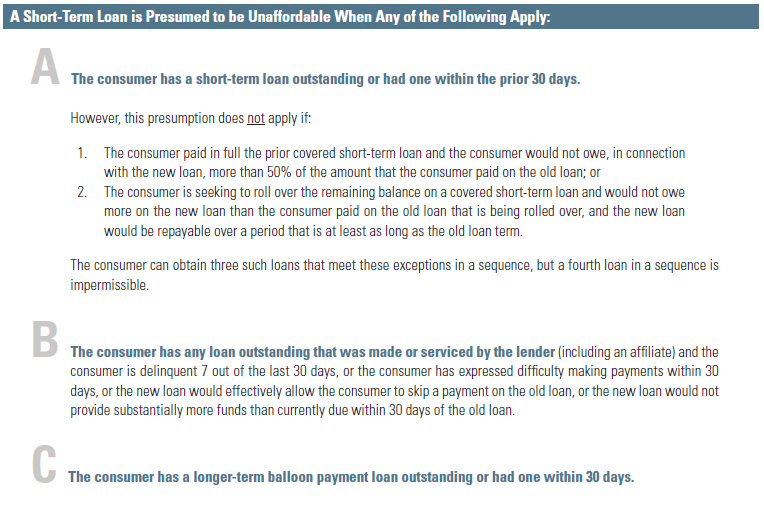

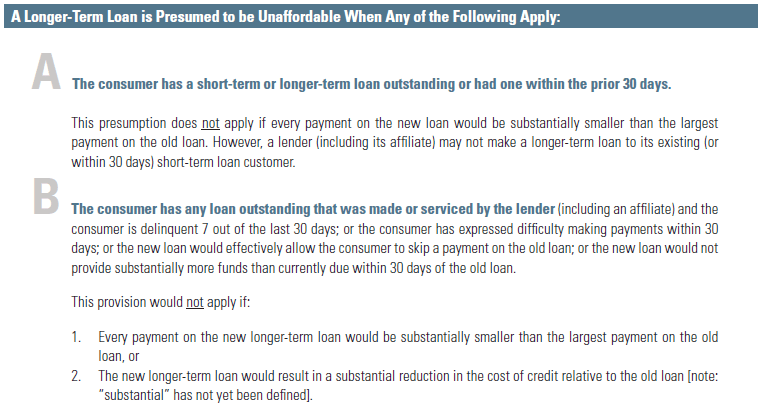

Determining a Loan’s Presumption of Unaffordability

A consumer is presumed not to be able to repay a loan in certain circumstances where the consumer already has, or recently had, a covered loan, even if an otherwise reasonable analysis determines that the consumer would be able to do so. The presumption could be overcome, however, if, based on reliable evidence, the consumer would have sufficient improvement in financial capacity such that the consumer will have the ability to repay the new loan according to its terms despite the characteristics of the prior loan.

Potential Opportunities and Traps for Lenders

OPPORTUNITIES

| → | Lenders may wish to make covered loans that take advantage of certain exemptions to the ATR analysis requirement. We will discuss those options in future articles. |

| → | Lenders also may wish to obtain and rely on statistical data obtained from government or private sources to model basic living and housing expenses. These sources, as well as underwriting software, would help to drive automation of the ATR determination. Of course, vendors will develop that software only if they anticipate the existence of a sufficient market of potential buyers, which is problematic given the CFPB’s prediction that the Rule will reduce the number of lenders in this space. |

TRAPS

| × | Basic Living Expenses The Rule allows for discretion in several critical places. Lenders would be expected to use their judgment, and have significant flexibility, in calculating the amount of a consumer’s basic living expenses. If those expenses are, in fact, estimated, and not determined by asking each consumer about his or her expenditures, the estimate must be reasonable and accurate. Otherwise, the residual income calculation, and thus the ATR determination, would not be accurate. Additionally, the policies and procedures that guide the determination need to be carefully followed—because missing an expense, like daycare, could swallow any residual income that appeared to be sufficient. |

| × | Major Financial Obligations Additionally, the housing expense could be verified by a transaction record. It also could be verified by “an amount determined under a reliable method of estimating a consumer’s housing expense based on the housing expenses of consumers with households in the locality of the consumer.” If the amount is inaccurately estimated, the error could affect the residual income calculation. If that were to happen, lenders could approve consumers who were unable to meet the Rule’s ATR standard. |

| × | Net Income Finally, when calculating a longer-term loan consumer’s ATR, a lender is required to take into account the possibility of volatility in net income and basic living expenses. A lender may account for this either by building a reasonable cushion into the residual income determination, or by determining that a particular consumer is unlikely to experience such volatility. A cushion appears to be the conservative choice—although the appropriate size of the cushion was not specified. For example, lenders may find using income sources like tips, bonuses, and anticipated tax refunds particularly volatile, and thus it may be unreasonable to base an ATR determination on them, at least without an appropriate cushion. If lenders opt to determine that volatility will not exist, their policies and procedures should accurately describe when it is reasonable to make that assumption, and those policies and procedures should be followed carefully. |

Anticipated CFPB Compliance and Enforcement

This Rule is unlike previous ATR requirements promulgated by the CFPB. Under the Rule, it would be per se unfair and abusive to make a covered loan that is inconsistent with the Rule’s ATR provisions. After the effective date, which we estimate will be sometime in late 2018, plus a reasonable time for lenders to make a few loans subject to the Rule, the CFPB is likely to begin examining lenders for compliance.

Accordingly, we expect the CFPB to significantly revise and reissue its current short-term, small-dollar examination procedures in advance of the Rule’s effective date. Once examinations begin, examiners will have an easy time determining compliance with many of the Rule’s elements. They will review lenders’ records, which must be maintained for 36 months, to identify whether the lender has evaluated each consumer’s net income, basic living expenses, major financial obligations, residual income, and total loan payments. They will identify whether lenders obtained a consumer’s written statement and appropriate verification evidence.

It is also fairly easy to determine whether lenders have followed their own policies and procedures—and whether a written policy and procedure exists (and of course, when it was adopted). The examiners are also likely to evaluate a lender’s compliance management system to determine whether it is capable of preventing, identifying, and remediating violations of this Rule and potential harm to consumers. Presumably, CFPB enforcement attorneys will also have an interest in lenders’ compliance with the Rule. Consequences for regulatory violations may be serious, especially given the attention this area will receive.

Finally, the CFPB most likely will conduct a file review to evaluate whether lenders have reasonably determined if consumers had the ability to repay covered loans. Because the calculation may be based, at least in part, on estimated or derived figures, this is not a straightforward evaluation. Consequently, if a lender’s rates of delinquency, default, or reborrowing are significantly higher than those of similar lenders, the CFPB could view that fact as evidence that the lender may be systematically underestimating amounts that consumers generally need for basic living expenses, or is in some other way overestimating consumers’ ability to repay. It is also likely that comparative data regarding those rates will be used to prioritize lenders for examination.

We anticipate that a lender may have reasonable procedures that it follows, but whose customers nevertheless default at higher rates. That result is unfortunate—unless the variance can be explained based on borrower, loan program, or business model characteristics that are unrelated to ATR. The concept is roughly analogous to a fair lending review: numerical outliers that cannot be explained away by other factors may result in a violation of law. For that reason, lenders should pay careful attention to their portfolios’ performance over time and adjust their ATR models accordingly.

Conclusion

The CFPB expects a lender’s ATR determination to be grounded in reasonable inferences and conclusions in light of information the lender is required to obtain or consider. In practice, the CFPB’s expectation requires time-intensive and costly underwriting policies and procedures that are not consistent with the current culture and approach of the payday, title loan, and installment loan business models. Those business models, which are predicated on simplicity and borrower convenience, are unlikely to be viable under the Rule in their current structures. As mentioned above, the Rule offers lenders the option of some alternatives to conducting an ATR analysis. We will publish additional articles analyzing those alternatives, and the Rule’s other requirements, in the coming weeks.

Click here to download this alert as a PDF.

For further information on this topic, please contact a member of the firm’s Consumer Financial Services Group.